The EH-lites wanted Build Back Better. Did you know BUILD BACK BETTER WAS ABOUT 15-MINUTE CITIES.

Kamala on inflation: BUILD BACK BETTER WAS SUPPOSED TO MAKE IT LESS EXPENSIVE FOR PEOPLE TO LIVE.

Ask yourself America if that happened.

Build back better!!!

This is article is from c40 cities knowledge hub. Yes the build back better was in their eh-lites documents front and centre as an opportunity to build us into 15 minute cities.

BUILD BACK BETTER IS 15 MINUTE CITIES.

https://www.c40knowledgehub.org/s/article/How-to-build-back-better-with-a-15-minute-city

“How to build back better with a 15-minute city

Author(s):

C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group, C40 Knowledge Hub

Jump to:

Appetite for more liveable, people-oriented cities is driving a surge of interest in the ‘15-minute city’ – an intuitive, adaptable and popular vision of urban living that already takes many names and shapes around the world. Leading examples include Bogotá's Barrios Vitales, Portland’s Complete Neighbourhoods and Melbourne’s 20 Minute Neighbourhoods, as well as the Paris 15-Minute City that captured international attention in the wake of the pandemic.

We have received a great deal of interest in our article How to build back better with a 15-minute city, which was published here in July 2020 as part of Spotlight On: A green and just recovery. In May 2021, we released an updated and expanded set of articles on this topic in Spotlight On: 15-minute cities, which unpacks what this approach offers and explains four key principles to guide the development and implementation of a 15-minute city vision. Each article draws on the good-practice ideas and experience of cities leading the charge and highlights a host of resources that dig deeper.

You can still find our original article below, but we recommend exploring Spotlight On: 15-minute cities to learn more. The five articles that make up our 15-minute city Spotlight are:

Why every city can benefit from a ‘15-minute city’ vision. From widened sidewalks and expanded bike networks to outdoor dining in space once used for parking, elements of the 15-minute city helped to manage the impact of COVID-19 in many places globally. The 15-minute city approach offers a way to build on positive changes to boost local economies and deliver lasting health, wellbeing, equity and climate benefits. This article highlights cities already implementing 15-minute city-style visions, plans and programmes, and explains more about why your city should join them.

15-minute cities: How to create ‘complete’ neighbourhoods. A successful 15-minute neighbourhood is ‘complete’ with core services and amenities that residents can easily walk or cycle to. This includes community-scale education and healthcare, essential retail like grocery shops and pharmacies, parks for recreation, working spaces and more. Many cities include neighbourhoods that deliver this, but they tend to be concentrated in central or wealthier areas. This article explains how cities can improve access to services in all neighbourhoods, starting with the most underserved. It looks at updates to planning and zoning rules that are critical to meeting these objectives in the longer term, and ways to bring more rapid change.

15-minute cities: How to ensure a place for everyone. Equity and inclusivity is central; a 15-minute city strategy must emphasise equal access to services, amenities and green space. This means designing approaches to actively reduce – and not risk compounding – social divides and inequalities. This article outlines ways in which cities can achieve this, including through engagement strategies involving a diverse mix of residents and stakeholders, policies to avoid displacement and ensure the provision of affordable housing, and by offering diverse, community-building amenities.

15-minute cities: How to develop people-centred streets and mobility. A 15-minute city reimagines streets and public space to prioritise people not driving, building more vibrant neighbourhoods where walking and cycling are the main ways of getting around. It enables and encourages people to choose not to drive. This means reclaiming car-dominated space for more productive, social and community-building uses, upgrading walking and cycling infrastructure to better serve the daily, local trips of people of all ages, abilities and backgrounds, and expanding green space in every neighbourhood. This article looks at how.

15-minute cities: How to create connected places. A 15-minute city offers convenience and quality of life, but not isolation. Physical and digital connectivity must be at the heart of any 15-minute city strategy, and is especially critical for sprawling, car-dependent cities. This article sets out ways to improve the quality and equitability of public transport systems, digitalise city services and develop digital infrastructure to ensure everyone has internet access, as part of a 15-minute city strategy.”

Don’t miss they eyelite mashup Trudeau Soros Obama et al.

“How to build back better with a 15-minute city

July 2020

In a ‘15-minute city’, everyone is able to meet most, if not all, of their needs within a short walk or bike ride from their home. It is a city composed of lived-in, people-friendly, ‘complete’ and connected neighbourhoods. It means reconnecting people with their local areas and decentralising city life and services. As cities work towards COVID-19 recovery, the 15-minute city is more relevant than ever as an organising principle for urban development. It will help cities to revive urban life safely and sustainably in the wake of COVID-19 and offers a positive future vision that mayors can share and build with their constituents. More specifically, it will help to reduce unnecessary travel across cities, provide more public space, inject life into local high streets, strengthen a sense of community, promote health and wellbeing, boost resilience to health and climate shocks, and improve cities’ sustainability and liveability. Learn more about the 15-minute city in the short clip below.

Carlos Moreno developed the 15-minute city concept in Paris and is a driving force behind its uptake in Paris and beyond. Watch his short TED talk here.

The concept of the 15-minute city is in direct contrast to the urban planning paradigms that have dominated for the last century, whereby residential areas are separated from business, retail, industry and entertainment.1 Nonetheless, most of the ideas and principles underpinning the 15-minute city are not new and most cities already contain areas that align with 15-minute city principles, even if by accident rather than by design. Some already have longer-standing urban development plans that strive for the very outcomes sought by the 15-minute-city model, extending its benefits across the whole city, for everyone. In 2020, the 15-minute city concept has gained momentum. More cities are now embracing this model to support a deeper, stronger recovery from COVID-19 and to help foster the more local, healthy and sustainable way of life that many of their citizens are calling for. Here are ideas and advice on how to build your 15-minute city vision and how to implement it.

First, establish a citywide 15-minute city vision

The core principles of a 15-minute city

Residents of every neighbourhood have easy access to goods and services, particularly groceries, fresh food and healthcare.

Every neighbourhood has a variety of housing types, of different sizes and levels of affordability, to accommodate many types of households and enable more people to live closer to where they work.

Residents of every neighbourhood are able to breathe clean air, free of harmful air pollutants, there are green spaces for everyone to enjoy.

More people can work close to home or remotely, thanks to the presence of smaller-scale offices, retail and hospitality, and co-working spaces.

The 15-minute city is a flexible concept that municipalities can tailor to their city’s culture and circumstances and to respond to specific local needs. Start by establishing a vision or goal, setting out what you want to see in all city neighbourhoods and what you want the city as a whole to look like, guided by the principles of the 15-minute city (see box). Next, collect data and seek participatory input from people across the city to map out the presence and absence at neighbourhood level of the amenities, businesses, job types, public spaces and other elements that have been identified as core to your city’s 15-minute city vision. Collecting neighbourhood-level geo-spatial data is an essential step in assessing needs at a hyperlocal scale, to inform the design and implementation of appropriate measures that can transition towards 15-minute city principles. You can draw on datasets about demographics, amenities, green space, groceries and retail, or any other information helpful to developing local policies.

Using this information, translate your citywide vision into a plan for each neighbourhood, focusing first on those that are furthest away from the goal. It is critical that lower-income neighbourhoods and others that are most underserved are prioritised for investment in 15-minute-city programmes, and that their residents and local businesses are involved in designing measures for improvement. Portland’s plan is one good example of this.2”

“A 15-minute city vision is usually established at the mayoral (or equivalent) level and can be linked to a transit-oriented development plan, urban development plan or equivalent land-use plan. Taking a participatory, inclusive approach to this process is important to ensure the plan is grounded in the city’s realities and has a broad base of support.

The 15-minute city is a complementary approach to transit-oriented development

Transit-oriented development promotes denser, mixed-used development around public transport services, enabling a large-scale shift away from reliance on private vehicles. Even in a successful 15-minute city neighbourhood, fast, frequent and reliable public-transport connections to other neighbourhoods and centres of work remain important to enable car-free access to jobs, friends and family, entertainment and more in other parts of the city. Read How to implement transit-oriented development for more on transit-oriented development.

Resources for co-creating an inclusive vision

How to engage stakeholders for powerful and inclusive climate action planning introduces approaches and tools for co-creation. Among them is the Inclusive Community Engagement Playbook, a detailed practitioners’ guide to everything cities need to know about how to deliver inclusive community engagement. Inclusive engagement processes can enable cities to identify local peoples’ priorities and craft a strong 15-minute city plan. The Playbook includes an innovative and diverse selection of tools of varying complexity to cater to cities with different needs and capacity, as well as case studies from cities around the world. The Playbook is available in English, Spanish, French and Portuguese.”

“Realise your 15-minute city vision through an inclusive engagement process

Following local engagement to shape your 15-minute city vision, businesses and residents should be invited to participate in the design and selection of local projects to realise it. Take steps to ensure that the opportunity to shape the vision and implementation of the 15-minute city reaches everyone ‒ particularly low-income and marginalised communities and local small and medium-sized enterprises, which are likely to have been hit hardest by the pandemic.

Cities with designated participatory budgets include:

Paris, where 10% of the City’s spending is determined by participatory budgeting processes at neighbourhood level. The city’s residents have the opportunity to participate in the design and selection of projects to be implemented in their own local area. This is one of the largest participatory budgets in the world.3

New York City, where the city’s participatory budgeting process ‘myPB’ has allocated $120 million to 706 community-designed projects over the last eight years, leading to improved local services.4”

“Improve walking and cycling infrastructure, including by reallocating street space to pedestrians and cyclists

With all but essential travel restricted during the COVID-19 crisis, walking and cycling have emerged as vital forms of mobility. These are physically distant, active, equitable and low-carbon modes of transport that are helping to facilitate safe local shopping and exercise and to alleviate pressure on public transport. As cities plan how to live safely with the virus in the medium to longer term, walking and cycling will be critical to enabling more people to travel safely and efficiently around their cities. Investment in walking and cycling now, while streets are quiet and traffic is reduced, will also quickly deliver a raft of other benefits for local economies, such as creating space for shops, restaurants and other pillars of public life that are essential to local economic recovery, as well as improvements in air pollution, equity and more.

There are many examples of cities around the globe that are responding to this opportunity to expand cycling and pedestrian infrastructure in the wake of COVID-19. Trailblazers include:

Bogotá and Berlin’s temporary bike lanes.

Seattle and San Francisco’s ‘open streets’.

Milan and Barcelona’s ambitious plans for road-space reallocation.

Lisbon and Mexico City’s public and private shared bike schemes, with many offering free or subsidised rides.5

The benefits of active travel are explained in more detail in Why shifting to green and healthy transport modes delivers vast rewards for cities.”

KAMALA ON THE RIGHT THING TO DO.BUILD BACK BETTER

“Create complete neighbourhoods by decentralising core services and developing a social and functional mix

Ensuring that everyone has access to everything they need in their own neighbourhood is at the core of the 15-minute city. This means that services such as community-scale healthcare and education, essential retail such as groceries and pharmacies, as well as parks for recreation and more need to be decentralised and present in each neighbourhood. Neighbourhood retail will also help to reduce crowding in large and central shopping areas, encouraging people to stay physically distant.

Most critically, cities should:

Ensure that shops selling fresh food are present in all neighbourhoods, eliminating food ‘deserts’. This could mean encouraging the trend for greater use of smaller neighbourhood food shops, where they exist, seen in many cities during the CODI-19 pandemic.

In 2019, as part of its Green New Deal, Los Angeles set a 2035 goal for all low-income residents to live within half a mile of fresh food, decentralising options.6

Lagos utilised closed schools as markets during the COVID-19 pandemic, so people could buy food and medicine close to their homes without having to travel long distances and to avoid large crowds of people in central markets.

Update the city’s plans and zoning to ensure that they require critical public services, infrastructure and green space to be accessible to all residents at neighbourhood level. Update the city’s plans and regulations ‒ such as comprehensive plans, district plans and zoning codes ‒ to ensure that they require each neighbourhood to be properly serviced in terms of green and open spaces, schools, small healthcare facilities and essential retail – particularly groceries, fresh produce and pharmacies. For example, this may mean ensuring the zoning codes allow for retail premises to open on the ground floor of every neighbourhood’s main street. Green space can be expanded in every neighbourhood by investing, for example, in transforming abandoned lots, schoolyards, parking spaces and road space into small or pocket parks. Cities can also implement mixed-use zoning to ensure a diversity of residential types, small-scale offices, repair shops, light industrial spaces, community gardens and more.

Promote affordable housing in each neighbourhood. Cities can do this by setting affordable housing requirements for new developments – an approach known as inclusionary zoning – or offer density bonuses or other incentives to developers for providing affordable units, for example. Cities must also ensure that any existing public or private affordable housing is preserved.

In 2020, Johannesburg adopted an inclusionary zoning policy that requires the provision of affordable units within multi-family developments, while granting additional density rights.

Los Angeles’ transit-oriented communities programme, passed in 2016, offers developers the opportunity to build more units, in addition to other incentives, if they include on-site affordable units within a short distance of key transit stops.

Implement planning measures to help complete neighbourhoods to thrive

To derive maximum value from the 15-minute city concept, cities should strive to go beyond meeting the basic needs of everyone within a 15-minute bike ride, to create local places where local people want to spend their time.

To develop local urban life and help neighbourhoods to thrive, cities can:

Promote active ground floors and bustling streets. In particular, updating zoning codes to mandate ‘active’ and ‘street-facing’ uses at ground level will help streets to thrive. In Paris, the Semaest is a semi-public agency whose role is to reinforce active ground floors and to revitalise neighbourhoods. For example, the agency has a ‘pre-emptive’ right to buy ground-floor space to repurpose for retail or commerce.

Encourage the flexible use of buildings and public space. This will help neighbourhoods to derive maximum value from their built environment, for the benefit of local people. Cities can promote a variety of uses for buildings, public spaces and infrastructure at different times of the day and week, or find (or help others to find) uses for public and private spaces during the day and night, during the week and at the weekend. The flexible use of space applies to more than just buildings; it is also linked to the flexible and reallocated use of road space for play, restaurants and more. It can foster the creation of spaces that serve multiple purposes at the same time. Over longer timescales, cities can also encourage modular design and ‘reversible buildings’ – buildings designed to be easily converted for different uses, reducing the need for demolition and rebuilding, as is the norm in most cities, with a significant impact on greenhouse gas emissions and resource use.

Paris is greening school playgrounds and granting residents access outside school hours for recreation, community gardening and to escape the summer heat. Paris is also building its first zero-carbon neighbourhood, with 100% of the spaces designed to be reversible and adaptable for different uses over time.

Many public schools in New York City allow food stalls and farmers markets to use their parking lots and schoolyards on weekends.

Flexible use of space and decentralisation to support the reopening of night-time venues

Many of the hardest-hit industries during the COVID-19 pandemic are those in the night-time economy – restaurants, bars, hotels, clubs and other businesses in the hospitality, nightlife, leisure and entertainment industries. During emergency response periods, many cities are supporting these businesses through tax, rent and utility freezes, among other measures – read more in Mitigating the economic impact of COVID-19. To help these businesses to operate at near-normal capacity while we live with the virus, some cities are making public space and road space available to them while capacity within their usual premises is reduced to facilitate physical distancing. In New York City, for example, 6,500 restaurants have applied for the city’s outdoor dining initiative, launched on 22nd June; the Department of Transportation has produced an interactive map to help New Yorkers to find them.7

To further support businesses in the night-time economy, cities could support them to reimagine how the nightlife scene and venues will operate in space and time. Ideas put forward at a Global Platform for Sustainable Cities webinar on this topic included decentralisation towards a more neighbourhood-focussed approach to reduce night-time congestion in city centres, and more flexible opening hours to allow use of venues at all times of day ‒ thinking of the city in 24-hour terms. For example, De School is a 24-hour licensed venue introduced to deal with excess tourism in the centre of Amsterdam; during the day, the venue is a café and library; at night, it turns into a club.

Encourage teleworking and service digitalisation to limit the need for travel

During the COVID-19 crisis, many people in many sectors are working from home, and many city governments have quickly shifted to increased online or telephone-based service delivery. Those able to work from home – or from a nearby co-working space ‒ can be encouraged and supported to do so in the longer term, to reduce COVID-19 transmission by reducing travel across the city while we live with the virus and to reduce traffic on the roads. Facilitating remote working and maintaining digitalised public services will also help cities to mitigate the impact of strict lockdown physical-distancing measures in the event of a second outbreak.

Continued high rates of teleworking will also enable more people to spend more time within their own or nearby neighbourhoods, further supporting local shops, cafes, restaurants and other street-front commerce, creating more local jobs.

City governments can support this by:

Increasing the digital offering of service and leading by example. London and Milan introduced new virtual outpatient healthcare programmes to support patients through the lockdown and plan to expand their telehealth infrastructure in future. Other cities, such as Phoenix, Rome and Athens, intend to continue their improved online government services as lockdown is eased and/or plan to keep a proportion of city staff working from home.

Consulting business leaders to understand the barriers to remote working.

Increasing the provision of widespread wi-fi and high-speed internet throughout the city, either through direct investment or working with private partners, as appropriate locally. If this infrastructure is built and operated privately, cities may be able to introduce regulation to require certain speeds or incentivise upgrades.

Promoting neighbourhood co-working spaces by creating these workspaces directly and/or supporting the creation of privately or community-run workspaces. Cities can upgrade and repurpose city-owned buildings by expanding the role of libraries and communities and involve workspace providers in mixed-use development planning, for example.8 London’s Creating Open Workspaces guide gives more information and examples; London had the largest growth in co-working spaces of any city in the world in 2019.9

Cities with 15-minute city-style visions, plans and programmes include:

Portland, Oregon, where the 2015 Portland Climate Action Plan sets a 2030 Complete Neighborhoods goal for 80% of residents to be easily able to access all their basic daily non-work needs by foot or bike, and to have safe pedestrian or bicycle access to transit.10 Portland’s indicators of neighbourhood completeness include distance from bike routes and transit services, distance from a neighbourhood park and community centre and the quality of sidewalks. The Plan prioritises underserved, low-income neighbourhoods for complete neighbourhood improvements.11

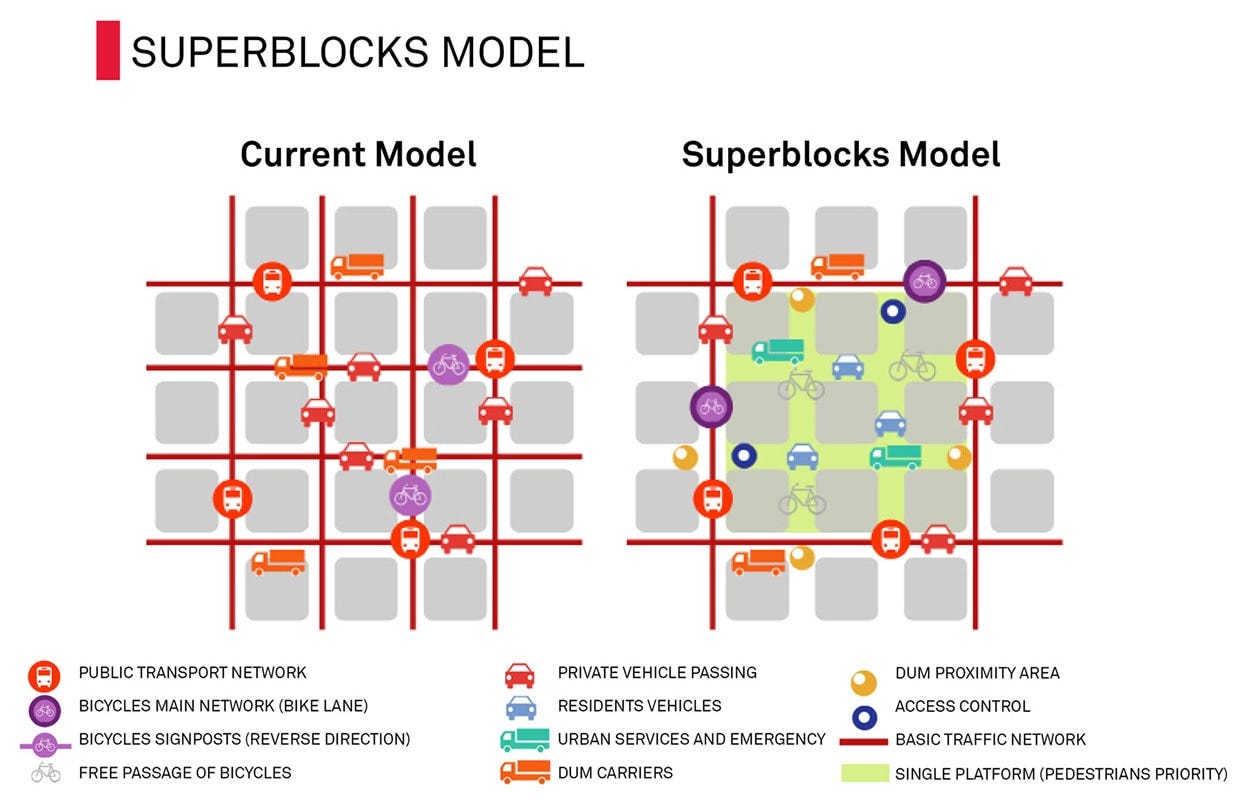

Barcelona has a superblocks system that modifies road networks within 400x400 metre blocks to improve the availability and quality of public space for leisure and community activities and for pedestrians and cyclists.12 Hear about the superblocks from Ada Colau, Mayor of Barcelona, in We have the power to move the world: a mayors’ guidebook on sustainable transport and from community organisations, superblock residents and others involved in the process in this eight-minute video. Learning from the successes of Barcelona and Vitoria-Gasteiz, which has also implemented superblocks, in June 2020 Madrid announced plans to pilot the superblock approach as part of its transition to a ‘city of 15-minutes’ to support the city’s revival following the pandemic. The superblock measures are cheap and reversible and will be designed and implemented in collaboration with residents.13

Source: Ajuntament de Barcelona14

Houston, Texas has proposed a Walkable Places ordinance to create six distinct central business districts, to reduce commuter traffic across the city.15 The city is taking a polycentric approach to urban development, which is also aligned with 15-minute city principles and well suited to low-density, sprawling cities.

In Paris, ‘hyper-proximity’ and the 15-minute city were a key pillar of Mayor Anne Hidalgo’s successful 2020 re-election campaign. The approach is designed to cut air pollution and hours lost to commuting, improve Parisians’ quality of life help the city achieve its plan to become carbon neutral by 2050. Paris has already massively scaled-up construction of protected pedestrian and cycle ways and aims to turn the city into myriad neighbourhoods where you can find everything you need within a 15-minute walk or cycle from home.16 Mayor Hidalgo’s people-first plans include installing a cycle path on every street and bridge ‒ enabled in part by turning over 70% of on-street car parking space to other uses – increasing office space and co-working hubs in neighbourhoods that lack them, expanding the uses of infrastructure and buildings outside of standard hours, encouraging people to use their local shops and creating small parks in school playgrounds that would be open to local people outside of school hours to combat the city’s lack of public green space.17

In China, Shanghai, Guangzhou and other cities have included 15-Minute Community Life Circles in their masterplans. Chengdu is another city taking a polycentric approach to urban development: it has a Great City plan to create a smaller, distinct satellite city in its outskirts, where everything will be within a 15 minute walk of the pedestrianised centre and connected to current urban centres via mass transit.

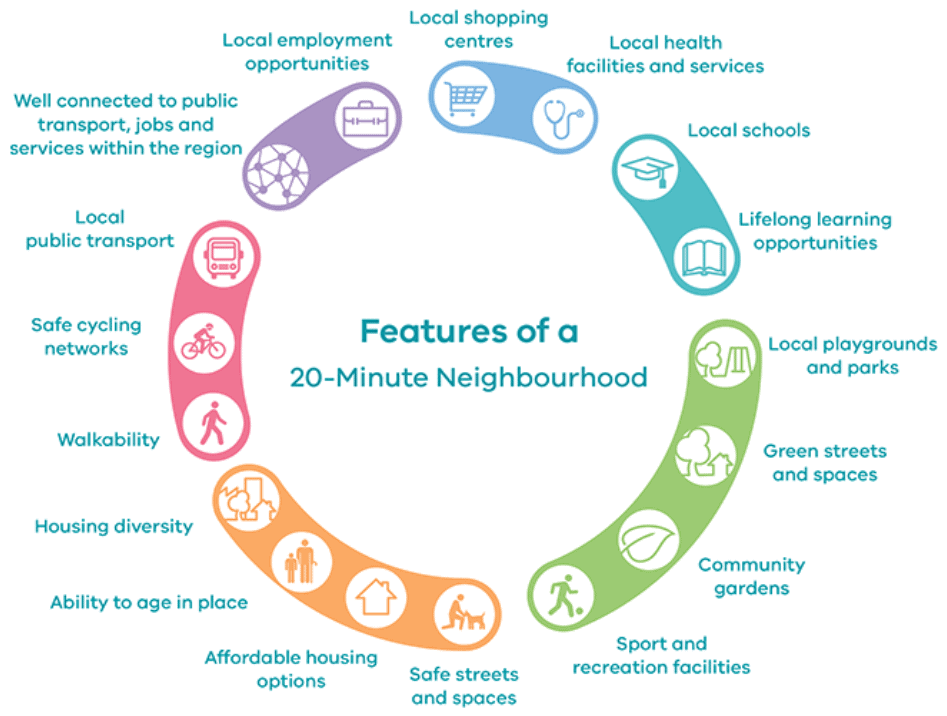

Melbourne’s plan for 2017‒2050 is guided by the principle of ‘20-minute neighbourhoods’, which are all about ‘living locally’ and creating inclusive, vibrant and healthy communities. In Melbourne, this is defined as giving people the ability to meet most of their daily needs (shown in the graphic below) within a 20-minute return walk from home (an 800m walkable catchment), with safe cycling and transport options. In 2018, Melbourne successfully piloted a programme to test 20-minute neighbourhoods in different local contexts and identify best-practice approaches to building community partnerships and strategies for delivery. Read the key findings and recommendations here.

Source: Victoria State Government18

In December 2019, Ottawa approved a 25-year urban intensification plan to create a community of ‘15-minute neighbourhoods’, aimed at turning the Canadian capital into North America’s most liveable mid-sized city, while planning for a population that is expected to at least double in size.19

Milan has cited the 15-minute city as a framework for its recovery, aiming to guarantee that essential services – particularly healthcare facilities – are within walking distance for all residents, while preventing a surge in car travel after the end of lockdown. Milan aims to create 35km of new bike lanes before the end of June and pedestrianise several school streets by September. It is also allowing some shops, bars and restaurants to use street space to serve customers outside, among other things. Madrid, Edinburgh and Seattle are other cities taking similar approaches as they emerge from COVID-19 outbreaks.”

You need to know that Build back better and 15 minute cities are connected. you heard it from their mouths. They are using the opportunity granted to them to universally move the 15 minute city.

Build back prison. better.

This all sounds wonderful for people who love living in the city. Not...

But seriously, what about people like me who have been living rural and have ZERO plans to ever live in a city?

Fuck that!

The question remains: How do we recover from this? We did not consent to these decisions. They were made without our knowledge.