STALIN'S NANNY, and Covid Zero Communist for Boris in the UK now behind the systemic TRANSFORMATIVE CHANGE IN CITIES

According to Daily Mail “the super-rich Communist Susan Michie is so militant that her fellow Marxists once searched her baby's pram for subversive literature.“

Image of Communist at the WHO Susan Michie.

“They lifted the tiny infant out of the way, to check that the future Professor of Psychology was not smuggling ultra-hardline propaganda into a crucial conference.”

Commies in Universities and Commies in the Government

According to Daily Mail, she was a “senior adviser to Boris Johnson's Tory Government, a regular participant in the official Sage committee and the SPI-B committee, which have had such influence over the handling of Covid.”

Is that Trudeau’s father on the wall? Image below from Daily Mail.

Why would the British Government pick a long avowed communist to decide on its Hard core lock down and oppression of freedoms during covid. Well if the shoe or fits. She was made a senior member of the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (Sage-Another one of their BARF acronyms) as well as other groups guiding Ministers and worse was given voice often through the BBC and ITV to propagate her pink notions of people repression.

This woman known as Stalin’s nanny is dedicated to establishing a new socialist order in her home country and AROUND THE WORLD.

She was a dangerous zealout of the 'Zero Covid' strategy which preferred repressions over reasonable living. Her goal was repression for the sake of repression (so SAGE of her). She wanted people locked up for longer, social-distancing rules imposed indefinitely and overseas travel curbed. But she can achieve this in her next role with the WHO.

(An interesting FOI is who are card carrying communists in our governments and NGOs, hob knobbing with the rich means using the word comrade a lot and conspiring to bring about identity politics to insert themselves in the haywire they create)

Here is Stalin’s Nanny presenting a webinar or controlling humans through AI.

The University Centre for Behavioural Change has an annual report.

It reviews:

“Examples of our 2022 translation of behavioural expertise to address critical global problems are:

Covid19: participated in the UK’s Scientific Advisory Group in Emergencies, Lancet Commission on Covid19 and three research projects on behavioural aspects of Covid19, including the weekly national survey commissioned by the Department of Health and Social Care (Professor Susan Michie & Dr Fabiana Lorencatto).

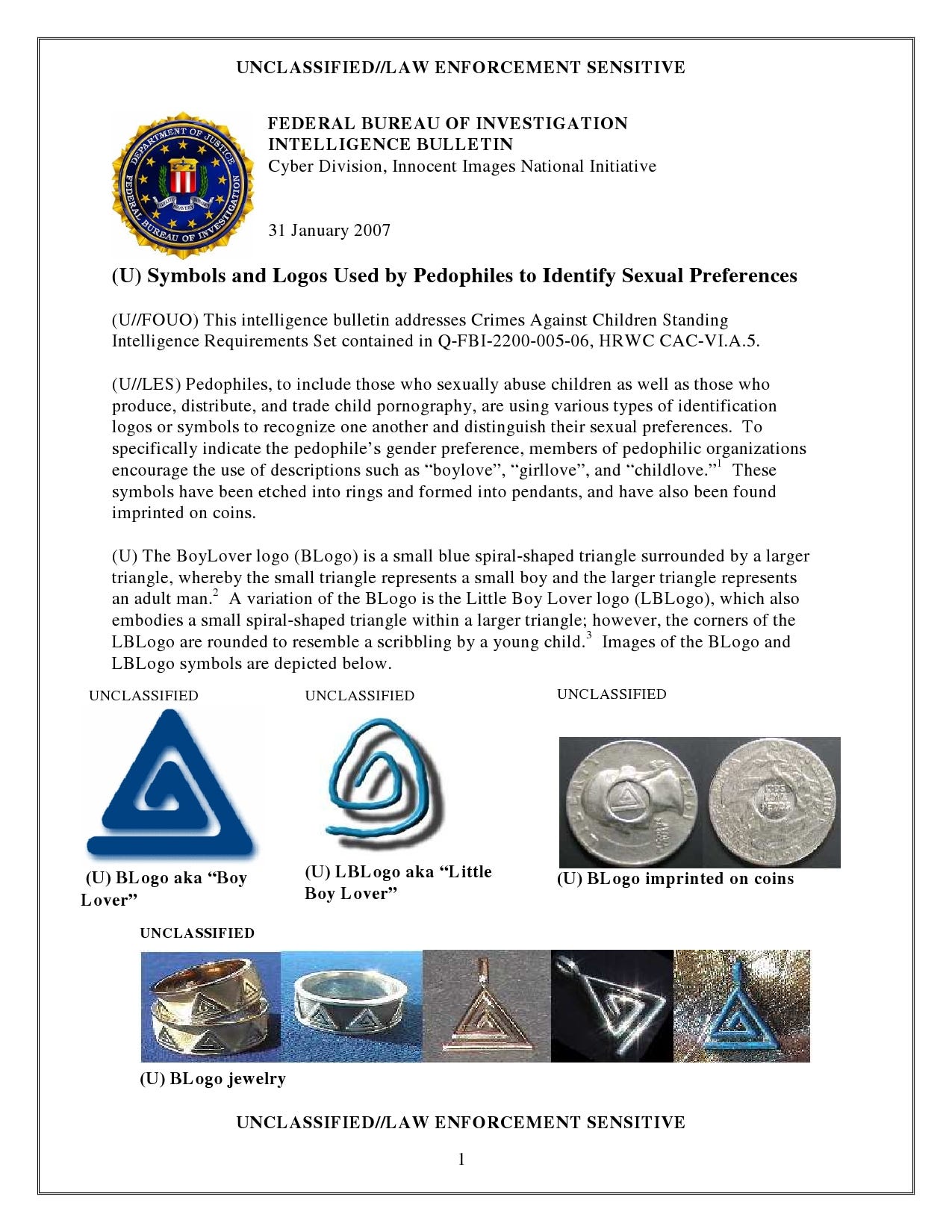

Stalin’s Nanny is working for an organization that picked a Logo that looks like the FBI’s logo for Pedophiles. What a creepy coincidence. AGAIN. The lock in you homers have some weird associates. I hope she wasn’t named Stalin’s nanny for what she did to children.

When you read through booklet, their intent is to figure our how best to scare us back into our homes, out of our rights.

STOP BEING SCARED. IT LITERRALY IS THEIR FAVORITE TOOL IN THEIR BOX. Just refuse not only to bow down, but to be scared. Being scared prevents the counter movement’s effectiveness. Empower each other.

“Abstract

Background: Environmental improvement is a priority for urban sustainability and health and achieving it requires transformative change in cities. An approach to achieving such change is to bring together researchers, decision-makers, and public groups in the creation of research and use of scientific evidence.

Methods: This article describes the development of a programme theory for Complex Urban Systems for Sustainability and Health (CUSSH), a four-year Wellcome-funded research collaboration which aims to improve capacity to guide transformational health and environmental changes in cities.

Results: Drawing on ideas about complex systems, programme evaluation, and transdisciplinary learning, we describe how the programme is understood to “work” in terms of its anticipated processes and resulting changes. The programme theory describes a chain of outputs that ultimately leads to improvement in city sustainability and health (described in an ‘action model’), and the kinds of changes that we expect CUSSH should lead to in people, processes, policies, practices, and research (described in a ‘change model’).

Conclusions: Our paper adds to a growing body of research on the process of developing a comprehensive understanding of a transdisciplinary, multiagency, multi-context programme. The programme theory was developed collaboratively over two years. It involved a participatory process to ensure that a broad range of perspectives were included, to contribute to shared understanding across a multidisciplinary team. Examining our approach allowed an appreciation of the benefits and challenges of developing a programme theory for a complex, transdisciplinary research collaboration. Benefits included the development of teamworking and shared understanding and the use of programme theory in guiding evaluation. Challenges included changing membership within a large group, reaching agreement on what the theory would be ‘about’, and the inherent unpredictability of complex initiatives.

Corresponding Author: David Osrin

Competing Interests: No competing interests were disclosed.

Grant Information: This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust through the Our Planet, Our Health award, ‘Complex Urban Systems for Sustainability and Health (London Hub)’ [209387, https://doi.org/10.35802/209387] and a Senior Clinical Research Fellowship [206417, https://doi.org/10.35802/206417] to DO. KZ is funded by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Public Health Research (SPHR) PhD Studentship [PD-SPH-2015]. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Open Access Copyright: © 2021 Moore G et al. This is an open access work distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

First Version Published: 19 Feb 2021, 6:35 (https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.16542.1)

Latest Version Published: 14 Jul 2021, 6:35 (https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.16542.2)

Introduction

We describe the development of a programme theory for Complex Urban Systems for Sustainability and Health (CUSSH), a four-year Wellcome-funded research collaboration between six cities on three continents and 13 institutions. The aim of the programme is to stimulate city transformation for improved environmental quality, sustainability, and health by bringing together groups of researchers, decision-makers such as policymakers, public health, and built environment professionals, and public groups in the development and use of research evidence. International multi-partner transdisciplinary programmes are increasingly desired and supported by research funders and government bodies, but there is a need to understand ‘what works’ in practice. Despite the interest in such programmes, difficulties can arise when researchers from different disciplines work with each other and with partners from other sectors1,2.

Transdisciplinary research

Transdisciplinary research is a challenging undertaking. Defined as ‘an integrative process whereby scholars and practitioners from both academic disciplines and non-academic fields work jointly to develop and use novel conceptual and methodological approaches that synthesize and extend discipline-specific perspectives, theories, methods, and translational strategies to yield innovative solutions to particular scientific and societal problems’3, it requires individuals with diverse backgrounds to draw on different sources and forms of knowledge at scales from local to global4. Multiple partners need to interact in different capacities and at different levels to generate and use findings within complex social and political systems and sometimes in different geographical contexts5. The development of a programme theory was an opportunity to examine how a cross-cultural, geographically dispersed collaboration with many moving parts might ‘work’6, both in achieving its aim of promoting city health and sustainability, and in understanding the processes and outcomes of transdisciplinary research.

Programme theory

Programme theory describes a variety of ways of developing a model that links programme inputs and activities to a chain of intended outputs and observed outcomes, and then uses the model to guide evaluation7,8. This kind of theory-based evaluation often rests on logic models or theories of change9. Complex interventions can be difficult to evaluate because they are based on poorly articulated assumptions6. A programme theory, therefore, seeks to open the “black box” between inputs and outputs10. Complex programmes—with multiple components, uncertain pathways, and emergent outcomes—present a challenge to the development of programme theories and subsequent evaluation. Their structure often includes several layers working simultaneously: individuals, communities, local, regional, and national government. It includes a range of perspectives, involves variability in delivery processes, and is of broad scope in real-world settings. If, however, we want to understand the success of such programmes and how they can be constructed, we need to understand their mechanics. Developing a programme theory can help investigate and evaluate the implementation process and the means by which change is brought about11. Despite the challenges, numerous examples in practice illustrate the possibilities of developing useful programme theories, although often from a single disciplinary or geographical perspective12–15. This paper contributes to the body of knowledge on developing programme theories, providing a detailed account of the process of development as an example for a complex, transdisciplinary programme.

Theory development as a process

Our work offers a rationale for developing a programme theory through collaborative and participatory processes and stresses its role as a provisional framework to guide evaluation. Developing a programme theory for CUSSH was important as a means of generating consensus between partners on the ways in which programme success might be evaluated. It required discussion of core assumptions, beliefs about the relationships between research and policymaking, and ideas about the kinds of indicators that might be used to measure progress and define “success”16. These discussions and the iterations of the programme theory can contribute to a process of team building, examining preconceptions and achieving a shared language. A collaborative process involving contributions from different forms of knowledge can help understand conceptual connections across the work of different partners, thereby guiding the corresponding collaboration with a purpose aligned with the agreed objectives. The clarifications that result from the process and the visual presentation of the theory contribute to a framework for programme evaluation7–9: the success of implementation (whether theoretical steps happened in practice) and whether the programme worked as expected (whether theoretical assumptions about how the activities would lead to change actually held)17–22. A programme theory and evaluation framework would enable the CUSSH team to compare experience with expectation and better understand the processes necessary to drive changes in health and environmental sustainability23.

For some programmes, a programme theory is developed and finalised at the start, although this is difficult in a complex programme in which new learnings are brought together. In practice, the development of a complex programme takes place as an iterative process. In this paper, we summarise the process and product, beginning with a sketch of the programme and then describing the development and content of its theory. We include some examples from our work in partner cities to illustrate the links between theory and practice. We hope that the paper contributes to developing knowledge about how to construct and evaluate a complex, transdisciplinary research programme.

The CUSSH programme

The programme’s aim is to enable city decision-makers to select and implement optimal actions for both sustainability and health. The objectives are to provide research evidence on the environmental and health benefits of large-scale city initiatives, to enable and support cities to deliver significant, measurable change by engaging and collaborating with stakeholders, and to find solutions that work in complex systems by fostering a systems thinking approach. The programme will also test the degree to which the use of scientific evidence and participatory engagement in decision processes can strengthen the envisioning, design, and implementation of transformational health and sustainability policies.

These objectives and aspirations are addressed in five broad, interacting work packages:

1. Examining existing evidence on the relative effectiveness of potential city actions.

2. Developing methods to track progress toward environmental and health goals.

3. Using modelling and microsimulation to develop rapid assessment tools for city actions.

4. Engaging decision-makers in partner cities in applying evidence-based systems thinking to help in policy and planning.

5. Engaging citizens in the decision-making process.

Central to the collaboration is partnership with six cities with different socio-political, geographical, environmental and city size contexts: Nairobi and Kisumu in Kenya, Beijing and Ningbo in China, and Rennes and London in Europe. Each geographical pair of cities includes a capital and a smaller city. The aim was to develop a matrix of contrasting income levels, environmental challenges, and scale, within pragmatic and logistical boundaries. The choice of capitals arose primarily as locations of academic research partners: Nairobi for the African Population and Health Research Centre, Beijing for Peking University, and London for University College London and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. The choice of smaller cities arose from existing connections: with Kisumu County for its interest in environmental initiatives to address its challenges of expansion, Ningbo, recommended because of its rapid expansion, and Rennes for its municipal commitment to urban health and sustainability.

City environments depend on human activity modifying the natural environment to create, connect and sustain systems for living and working. They are made up of two sorts of fabric: the “hard” fabric of buildings, infrastructure, and bounded open space, and the “soft” fabric of community, society, and governance (the ville and the cité)24 . Because achieving sustainability and health will both depend on changes to the built and social environments, the collaboration includes experts on hard fabric (engineering, building physics), soft fabric (urban sociology, behavioural science), public policy and decision-making (urban planning and public health), environment and health (environmental science, climate science, urban health, planetary health), and methodologies (modelling and simulation, participatory system dynamics, public engagement, programme evaluation, evidence synthesis).

The partnership agreed on three foundational ideas from the beginning: that transformative change in cities is necessary, that research evidence should inform policymaking and planning for change, and that cities are complex and require transdisciplinary solutions.

Transformative change in cities is necessary

Environmental improvement is a priority for both sustainability and health and actions to improve either have the potential to provide co-benefits and improve both25–29. However, city-level efforts at the scale necessary to meet sustainability goals or improve population health have been inadequate30–32. Actions have involved largely transitional changes, or piecemeal actions, which may be useful in developing capacity for change—in harnessing individuals, organisations, and society to develop and adapt—but are unlikely to be at a sufficient scale and pace to meet current imperatives. Radical and rapid shifts in infrastructural, behavioural, and operational systems are required to transform cities to meet health and sustainability needs. Table 1 summarises some general comparisons between urban change that we would define as ‘transitional’ and the type of urban transformation required to meet health and sustainability goals.

CHARACTERISTICS OF CHANGE

TRANSITIONAL TRANSFORMATIONAL REFERENCES

Research evidence should inform policymaking and planning

Policymaking is non-linear and scientific evidence–even if cited—often contributes little to the decision-making process33. Although research can inform and add weight to recommendations41, it has not often been used to inform urban policy directly42,43. Academics have begun to address this challenge through engagements with multiple stakeholders that examine trade-offs, feasibility, and effects in the short and long term44. These engagements aim to increase communication between researchers and time-poor policymakers45,46, using evidence to respond to local concerns, address a salient issue at the right time47,48, and tell a persuasive and relatable story with people’s lives at its centre43,49. In a systematic review of barriers to and facilitators of policymakers’ use of evidence1, the most frequent needs were to increase the dissemination and availability of research findings, to make them as clear and relevant as possible (particularly to users with limited experience of research methods and their interpretation), and to encourage collaboration between policymakers and researchers. A key theme is how academics build relationships with policymakers. A recent review by Oliver and Cairney notes that academics have strong incentives to influence policymaking, but may not know where to start50.

Cities are complex and require transdisciplinary engagement and a spectrum of methods

Cities provide examples of the ‘wicked’ problems characteristic of complex systems51,52. Understanding change in cities requires different disciplines to work together, incorporating a spectrum of methods, systems thinking, and participatory engagement43,53–55. Systems thinking is about incorporating a variety of ways of thinking and views about a problem or challenge to generate a more comprehensive understanding of cause-and-effect56. A complex view of cities means seeing parts of the system holistically as a set of elements whose interactions may affect the whole more than the parts, with properties emerging at different levels, causality operating both within and between levels, and people acting according to different rationales57. We took a structured approach to addressing sustainability and health in cities: clarifying the issues that need to be addressed, investigating their causes, developing solutions, and supporting implementation. The systems thinking approach helped us understand feedback systems, local networks, infrastructure, decision-making processes, and power relations. In a related effort to break the cycle of risk accumulation across sub-Saharan African cities, Dodman and colleagues provide a rationale for using a spectrum of methods to address a spectrum of risks, demonstrating in a wide-ranging multi-country programme of research the utility of mixed-methods approaches in planning for resilience58. They galvanised multidisciplinary expertise and multifaceted and collaborative research to gather empirical data and build a strong evidence base covering social, political, economic, biophysical, and hydrogeological systems in cities to provide a more solid base for planning and investment.

The need to work with such complex biosocial and technical systems has led to calls for transdisciplinarity28,59–63, encapsulated in ideas about the Science of Team Science64,65. Generally, working with cities is an attractive proposition because their political structures and decision-making powers can respond flexibly to challenges (city mayors, for example, have become prominent on the global stage), but achieving change will involve both city decision-makers and planners and other actors—formal and informal—who affect implementation. Table 2 summarises the different stakeholder groups involved.”

The WHO, a CCP leaning organization has Stalin’s Nanny running their organization on HOW TO SCARE THE SHIT OUT OF PEOPLE TO MAKE THEM DO WHAT WE WANT ADVISORY GROUP.

In case you wanted to know they want to bring in OPS to scare you. Knowledge is Power.

Be sure to watch and systematically share into communities this video.

https://rumble.com/v2uo9nk-c40-cities-the-future-of-urban-consumption-in-a-1.5c-world.html

Wellcome trust again, ha...well, they can "research" till they die, they are too anchored and locked in their bubble, things don't work and will not work as they expect. they will cause destruction, but they will not win or scare us.

The globalist seem to select the most eccentric, wacky, control seeking people to do their bidding. I would not consider myself a rebel, yet this is enough. I am a critical thinker. I want to know the pros and cons. I do not want the you have to do this or else.