“Some nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) reported that an environment conducive to free and fair elections was not in place prior to the election. There were reports of unfair government tactics, including intimidation of opposition candidates and supporters, and violence before and after the election that resulted in six confirmed deaths.

Civilian authorities generally maintained control over the security forces, although local police in rural areas, the Somali Region Special Police, and local militias sometimes acted independently.

The most significant human rights problems included harassment and intimidation of opposition members and supporters and journalists; alleged torture, beating, abuse, and mistreatment of detainees by security forces; and politically motivated trials.

Other human rights problems included alleged arbitrary killings; harsh and at times life-threatening prison conditions; arbitrary arrest and detention; detention without charge and lengthy pretrial detention; a weak, overburdened judiciary subject to political influence; infringement on citizens’ privacy rights, including illegal searches; alleged abuses in the implementation of the government’s “villagization” program; restrictions on freedom of expression, including continued restrictions on print media and the internet, assembly, association, and movement; restrictions on academic freedom; interference in religious affairs; restrictions on activities of civil society and NGOs; limited ability of citizens to change their government; police, administrative, and judicial corruption; violence and societal discrimination against women and abuse of children; female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C); trafficking in persons; societal discrimination against persons with disabilities; clashes between ethnic minorities; discrimination against persons based on their sexual orientation and against persons with HIV/AIDS; and limits on worker rights, forced labor, and child labor, including forced child labor. Impunity was a problem. The government, with some reported exceptions, generally did not take steps to prosecute or otherwise punish officials who committed abuses other than corruption.

Members of the security forces reportedly committed arbitrary or unlawful killings. From the end of the election campaign period on May 21 until the announcement of election results on June 22, opposition parties reported the death of six party members, including one candidate from the Blue Party.

The deaths occurred in the Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Region (SNNPR); Oromia; Amhara; and Tigray. The deceased included one supporter of an independent candidate, one member of the Blue Party, and four members of Medrek, an opposition coalition made up of four political parties.

One of the six was an accredited election observer for the Oromo Federalist Congress (one of four parties that make up the Medrek opposition coalition). The Ethiopian Human Rights Commission (EHRC) and the Ethiopian Federal Police Commission investigated the deaths and found no political motivation behind the killings

Shortly after the May 24 national elections, there were reports of violence between the residents of Hamer County of the South Omo Zone in the SNNPR and security forces that resulted in as many as 48 deaths. According to reports the drivers of the conflict in the South Omo Zone include economic marginalization of local communities, loss of traditional grazing lands to large-scale, government-financed sugar plantations, and restrictions on hunting.

On June 13 and 14, security forces reportedly opened fire on protesters, killing at least six and wounding several others. The demonstrators were participating in an unauthorized political demonstration in the Chilga district of the Amhara Region (North Gondar). Supporters of a small party representing the Kemant ethnic group refused to accept the election results, refuting the claim of a clean sweep by the Amhara National Democratic Movement, one of the four constituent parties of the ruling EPRDF.

The husband of the Italian MEP is killed

Image from CNA.

On November 19, students in the Oromia Region began protesting in opposition to the expansion of the city of Addis Ababa into the surrounding region of Oromia. The protests against land expansion, also known as the Addis Ababa Master Plan, spread to small towns and villages across the Oromia Region.

Some of the protests escalated into violent clashes between protesters and security forces, which allegedly used excessive force, resulting in dozens of deaths, including protesters and police officers. The protests and violence in the Oromia Region continued at year’s end. In October 2014 gunmen reportedly killed 126 police and civilians in the Gambella Region. The clash occurred between a group of ethnic Majanger and Ethiopian national and local security forces. In December 2014 officials charged at least 46 individuals, including officials from the Gambella regional government, with terrorist acts, and they were on trial at year’s end under the Anti-Terrorism Proclamation (ATP).

b. Disappearance

There were fewer credible reports than in previous years of disappearances of civilians after clashes between security forces and rebel groups. Opposition parties reported disappearances of party members and observers before and after the national elections on May 24; however, the EHRC later located some of those individuals. Many of those reported missing had fled to Kenya. Due to poor prison administration, family members reported missing individuals who were in custody of prison officials, but whom the families could not locate.

c. Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment

The constitution and law prohibit such practices; nevertheless, there were reports security officials tortured and otherwise abused detainees. In February, one of the Zone 9 bloggers on trial accused a prison guard of beating him and leaving him with his hands tied together throughout the night.

Victim of Gender Ideology: 400 Days in Prison for Refusing to Use LGBT+ Pronouns - ZENIT - English

The EHRC and an NGO investigated the incident. The Ethiopian Federal High Court summoned prison administration officials, but the defendant declined to submit his complaint in writing, as requested by the court. The Federal High Court regularly sought explanations from prison officials concerning allegations of mistreatment There were credible reports police investigators used physical and psychological abuse to extract confessions in Maekelawi, the central police investigation headquarters in Addis Ababa. Interrogators reportedly administered beatings and electric shocks to extract information and confessions from detainees.

The NGO Human Rights Watch (HRW) reported abuses, including torture that occurred at Maekelawi. In a 2013 report, HRW described beatings, stress positions, the hanging of detainees by their wrists from the ceiling, prolonged handcuffing, pouring of water over detainees, verbal threats, and solitary confinement at the facility. Authorities continued to restrict access by diplomats and NGOs to Maekelawi, although some NGOs reported limited access. The majority of the mistreatment reportedly occurred in detention centers like Maekelawi and police stations rather than federal prisons. According to NGO reports, thousands of ethnic Oromos, whom the government accused of terrorism, were arbitrarily arrested and in some cases reportedly tortured.

Prison and Detention Center Conditions Prison and pretrial detention center conditions remained harsh and in some cases life threatening. There were reports authorities beat and tortured prisoners in detention centers and police stations. Medical attention following beatings reportedly was insufficient in some cases. The country had six federal and 120 regional prisons.

A local NGO ran model prisons in Adama, Mekelle, Debre Birhan, Durashe, and Awassa; these prisons had significantly better conditions than those found in other prisons. There also were many unofficial detention centers throughout the country, including in Dedessa, Bir Sheleko, Tolay, Hormat, Blate, Tatek, Jijiga, Holeta, and Senkele. Pretrial detention often occurred in police station detention facilities, where conditions varied widely, but reports on conditions there indicated poor hygiene and police abuse of detainees.

Pro-life advocate's sentence to 57 months in prison, 3 years supervision to be appealed - CatholicVote org

Physical Conditions: Authorities sometimes incarcerated juveniles with adults. Prison officials generally separated male and female prisoners. Severe overcrowding was common, especially in prison sleeping quarters. The government provided approximately nine birr ($0.43) per prisoner per day for food, water, and health care, although this amount varied across the country. Many prisoners supplemented this amount with daily food deliveries from family members or by purchasing food from local vendors, although there were reports officials prevented some prisoners from receiving supplemental food from their families. Medical care was unreliable in federal prisons and almost nonexistent in regional prisons.

Prisoners had only limited access to potable water, as did many in the country. Water shortages caused unhygienic conditions, and most prisons lacked appropriate sanitary facilities. Many prisoners had serious health problems but received little or no treatment. There were reports prison officials denied some prisoners access to necessary medical care. Information released by the Ministry of Health in 2012 stated nearly 62 percent of inmates in jails across the country experienced mental health problems due to solitary confinement, overcrowding, and lack of adequate health-care facilities and services..

d. Arbitrary Arrest or Detention Although the constitution and law prohibit arbitrary arrest and detention, the government ignored these provisions. There were many reports of arbitrary arrest and detention by police and security forces throughout the country. On March 15, officials detained seven pastoralist and community leaders at Bole International Airport en route to participate in an agricultural workshop in Nairobi. Investigators later released four without charging them.

At year’s end the remaining three on trial were charged with terrorist acts under the ATP. In the period preceding the May 24 national elections, opposition parties reported extrajudicial and arbitrary detentions of opposition party members, candidates, and election observers. Authorities subsequently released most without charge, and some fled to Kenya.

Following weeks of protests throughout the Oromia Region that began in late November in opposition to the Addis Ababa Master Plan, NGOs and opposition party leaders reported violent clashes between protesters and security forces resulting in thousands of extrajudicial and arbitrary detentions.

Calgary pastor Derek Reimer faces 8 more charges (LL he got pushed at the drag queen story hour- but he gets arrested)

There were reports of security forces arbitrarily detaining students on university campuses in connection with the protests. According to opposition party leaders, security forces arbitrarily detained opposition party members and supporters and accused them of inciting violence. Role of the Police and Security Apparatus The Federal Police reports to the Ministry of Federal and Pastoralist Affairs, which is subject to parliamentary oversight.

Police Arrest 50 New Zealand Covid Protesters Inspired by Canada Truckers - Bloomberg

The oversight was loose. Each of the country’s nine regions has a state or special police force that reports to the regional civilian authorities. Local militias operated across the country in loose coordination with regional and federal police and the military, with the degree of coordination varying by region.

In some cases these militias functioned as extensions of the ruling party. Security forces were effective, but impunity remained a serious problem. The mechanisms used to investigate abuses by federal police were not known. The government rarely publicly disclosed the results of investigations into abuses by local security forces, such as arbitrary detention and beatings of civilians.

The government continued to support human rights training for police and army personnel. In 2014-15 the EHRC conducted training sessions for 4,165 police officers and prison guards on basic human rights concepts as well as rights of detained individuals as provided in the National Human Rights Action Plan.

The government continued to accept assistance from NGOs and the EHRC to improve and professionalize its human rights training and curriculum by including more material on the constitution and international human rights treaties and conventions. Arrest Procedures and Treatment of Detainees The constitution and law require detainees be brought to court and charged within 48 hours of arrest or as soon thereafter as local circumstances and communications permit. Travel time to the court is not included in the 48-hour period.

More than 250 arrested during lockdown protests in Australia - Los Angeles Times

With a warrant authorities may detain persons suspected of serious offenses for 14 days without charge and for additional 14-day periods if an investigation continues. Under the ATP police may request to hold persons without charge for 28-day periods, up to a maximum of four months, while an investigation is conducted.

New Zealand police clash with anti-vaccine protesters at parliament, over 120 arrested | New Zealand | The Guardian

The law prohibits detention in any facility other than an official detention center; however, local militias and other formal and informal law enforcement entities used dozens of unofficial local detention centers. A functioning bail system was in place. Bail was not available for persons charged with terrorism, murder, treason, and corruption. In most cases authorities set bail between 500 and 10,000 birr ($24 and $480), which most citizens could not afford.

Secret documents reveal how China mass detention camps work | AP News

The government provided public defenders for detainees unable to afford private legal counsel, but they did so only when cases went to court. There were reports that while some detainees were in pretrial detention, authorities allowed them little or no contact with legal counsel, did not provide full information on their health status, and did not allow family visits. There were reports officials held some prisoners incommunicado for weeks at a time. Arbitrary Arrest: The law permits warrantless arrests for various offenses including “flagrant offenses.” These include offenses in which the suspect is found committing the offense, attempting to commit the offense, or having just completed the offense.

China and Myanmar face Uighurs and Rohingya that are fighting back after years of oppression

The ATP permits a warrantless arrest when police reasonably suspect a person has committed or is committing a terrorist act. Authorities regularly detained persons without warrants. For example, in January and February, authorities arrested a group of 20 Muslims in Addis Ababa and Jimma. On August 17, they charged them under article 7 of the ATP for attempting to establish an Islamic state and inciting violence in an effort to force the government to free the Arbitration Committee Members. In 2012 authorities had arrested this group of Muslim community leaders after widespread protests against alleged government interference in Muslim affairs. The trial continued at year’s end.

On May 13, police arrested Mamushet Amare, ousted president of the All Ethiopian Unity Party, alleging he was behind unrest at a government-organized anti- Da'esh rally on April 22. After a court ordered his release on June 2, police rearrested Mamushet, citing a need to investigate his case further. On August 28, the Federal First Instance Court ordered Mamushet’s acquittal and release after his defense proved prosecution witnesses falsely testified against him. Pretrial Detention: Some detainees reported being held for several years without charge and without trial. Information on the percentage of the detainee population in pretrial detention and the average length of time held was not available. Lengthy legal procedures, large numbers of detainees, judicial inefficiency, and staffing shortages often caused trial delays.

The Secret History of FEMA | WIRED

In September, in keeping with a long-standing tradition of issuing pardons at the Ethiopian New Year, the federal government pardoned 238 prisoners, including 33 convicted of terrorism. Apart from two foreign journalists in 2012, this was the first time the federal government issued pardons to individuals convicted of terrorism. Regional governments also pardoned 12,941 prisoners in Amhara, Oromia, and Benishangul-Gumuz.

e. Denial of Fair Public Trial The law provides for an independent judiciary.

Although the civil courts operated with a large degree of independence, the criminal courts remained weak, overburdened, and subject to political influence. The constitution recognizes both religious and traditional or customary courts. Trial Procedures By law accused persons have the right to a fair public trial by a court of law “without undue delay,” a presumption of innocence, the right to be represented by legal counsel of their choice, and the right to appeal. The law provides defendants the right not to self-incriminate.

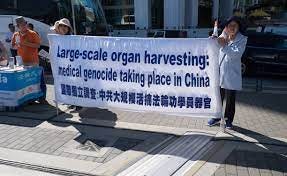

Former Uighur Surgeon Discloses Live Organ Harvesting in China

The law gives defendants the right to present witnesses and evidence in their defense, cross-examine prosecution witnesses, and access government-held evidence. The court system does not use jury trials. The government continued to train lower-court judges and prosecutors on effective judicial administration. Defendants were often unaware of the specific charges against them until the commencement of their trials; this meant defense attorneys were unprepared to provide an adequate defense. Authorities provided free interpretation as needed, and gave adequate time and facilities to prepare a defense. Defendants are not compelled to testify or confess guilt. The Public Defender’s Office, a federal institution, provided legal counsel to indigent defendants, although its scope and quality of service remained limited due to the shortage of attorneys.

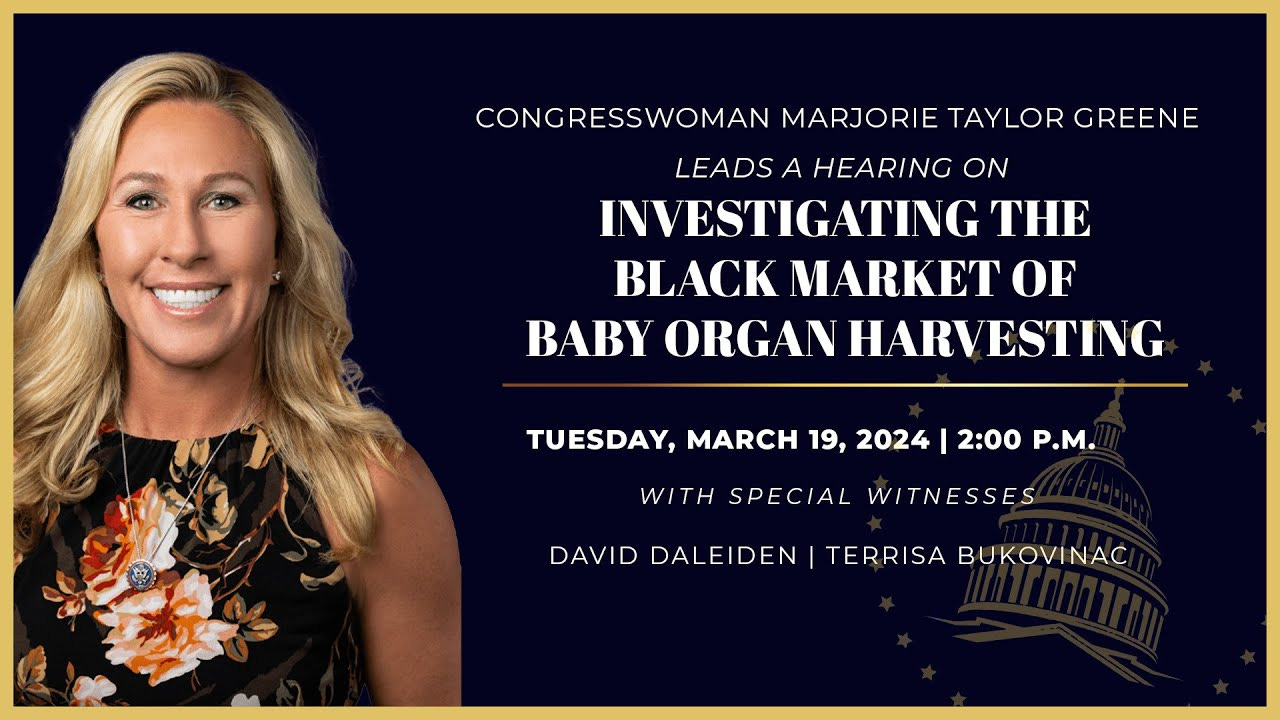

David Daleiden on Fetal Experimentation at University of Pittsburgh

Numerous free legal aid clinics around the country, based primarily at universities, provided services to clients. In certain areas of the country, the law allows volunteers, such as law students and professors, to represent clients in court on a pro bono basis Many citizens residing in rural areas had little access to formal judicial systems and relied on traditional mechanisms for resolving conflict.

On July 8 and 9, prosecutors dropped antiterrorism charges against three journalists and two bloggers from the Zone 9 blogging collective: Tesfalem Waldyes, Asmamaw Hailegiorgis, Edom Kassaye, Zelalem Kibret, and Mahlet Fantahun.

Moreover, the ATP permits warrantless searches of a person or vehicle when authorized by the director general of the Federal Police or his designate or a police officer has reasonable suspicion a terrorist act may be committed and deems it necessary to make a sudden search. Opposition political party leaders reported suspicions of telephone tapping and other electronic eavesdropping, and they alleged government agents attempted to lure them into illegal acts by calling and pretending to be representatives of groups--designated by the parliament as terrorist organizations--interested in making financial donations.

Ottawa’s new digital hate watchdogs would cost $200-million, PBO analysis says

The government reportedly used a widespread system of paid informants to report on the activities of particular individuals. Opposition members reported ruling party operatives and militia members made intimidating and unwelcome visits to their homes and offices. Security forces continued to detain family members of persons sought for questioning by the government.

(East Palestine derailment)

The national and regional governments continued to put in place the policy of Accelerated Development (informally known as “villagization”) plans in the Afar, Benishangul-Gumuz, Gambella, the SNNPR, Oromia, and Somali regions, which might include resettlement. These plans involved the relocation by regional governments of scattered rural populations from arid or semiarid lands vulnerable to recurring droughts into designated communities closer to water, services, and infrastructure.

(Maui Fire)

The stated purposes of accelerated development were to improve the provision of government services (i.e., health care, education, and clean water), protect vulnerable communities from natural disasters and attacks, and change environmentally destructive patterns of shifting cultivation. Some observers alleged the purpose was to enable the large-scale leasing of land for commercial agriculture. The government described the accelerated development program as strictly voluntary. The government had scheduled to conclude the program in 2015, but decide to continue it instead

(Jasper Fire)

International donors reported that assessments from more than 18 visits to villagization sites since 2011 did not corroborate allegations of systematic human rights violations. They found problems such as delays in establishing promised infrastructure and adequate compensation, as part of promises made to communities before their relocation. Communities and individual families appeared to have agreed to move based on assurances from authorities of food aid, health and education services, and land, although in some instances communities moved before adequate basic services such as water pumps and shelter were in place in the new locations. International human rights organizations, nevertheless, continued to express concern regarding the villagization process. Donors were mobilizing to continue monitoring of Accelerated Development sites and intend to report their findings to the government and the public.

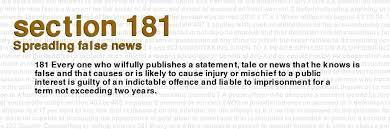

(THIS FALSE NEWS PROHIBITION IN CANADA WAS ELIMINATED JUNE 2019. INTERESTING TIMING)

Section 2. Respect for Civil Liberties, Including: a. Freedom of Speech and Press

The constitution and law provide for freedom of speech and press; however, authorities harassed, arrested, detained, charged, and prosecuted journalists and other persons whom they perceived as critical of the government, creating an environment where self-censorship negatively affected freedom of speech.

Opinion: The (re)education of Jordan Peterson - The Globe and Mail

Some journalists, editors, and publishers fled the country, fearing probable detention. At year’s end at least nine journalists and bloggers remained in detention; of these, two were arrested in February and charged in August. A journalist was convicted under the ATP and sentenced to seven years in prison. Authorities detained one journalist for three weeks and then released him without charge.

In July, three journalists and two bloggers, detained since April 2014, were released from prison after the prosecution dropped terrorist charges. In October, four bloggers, including one in absentia, were acquitted of terrorist charges, and the court reduced charges for another blogger from being a terrorist to criminal code charges. Freedom of Speech and Expression: Authorities arrested and harassed persons for criticizing the government. NGOs reported cases of torture of individuals critical of the government.

The government attempted to impede criticism through various forms of intimidation, including detention of journalists and opposition activists and monitoring of and interference in the activities of political opposition groups. Some persons feared authorities would retaliate against them for discussing security force abuses. Press and Media Freedoms: Independent journalists reported logistical challenges using government printing presses. Access to private printing presses was scarce to nonexistent. In most cases articles cited as examples of incitement were mainly critical of government action. In Addis Ababa 15 independent newspapers had a combined weekly circulation of more than 71,000 copies. State-run newspapers had a combined circulation of more than 80,000 copies. Most newspapers were printed on a weekly or biweekly basis, with the exception of the state-owned Amharic and English dailies and the privately run Daily Monitor.

Government-controlled media closely reflected the views of the government and the ruling EPRDF. The government controlled the only television station that broadcast nationally, which, along with radio, was the primary source of news for much of the population. Six private FM radio stations broadcast in the capital, one private radio station broadcast in the northern Tigray Region, and at least 19 community radio stations broadcast in the regions. State-run Ethiopian Radio had the largest broadcast range in the country, followed by Fana Radio, which was reportedly affiliated with the ruling party.

The government periodically jammed foreign broadcasts. The law prohibits political and religious organizations and foreigners from owning broadcast stations.

Violence and Harassment:

The government continued to arrest, harass, and prosecute journalists. This included the conviction in July of three persons associated with the defunct Muslim Affairs magazine under the ATP and prosecution of two others who worked for the defunct Bilal Radio. In 2014 there were allegations of bloggers and journalists being abused and their rights violated in the Maekelawi detention center. On February 18, police detained two journalists affiliated with Bilal Radio.

The Federal High Court charged the journalists under the ATP in August and denied them bail. Their trial continued at year’s end. Censorship or Content Restrictions: Government harassment caused journalists to avoid reporting on sensitive topics. Many private newspapers reported informal editorial control by the government through article placement requests and calls from government officials concerning articles perceived as critical of the government. Private sector and government journalists routinely practiced selfcensorship. Several journalists, both local and foreign correspondents, reported an increase in self-censorship. The government reportedly pressured advertisers not to advertise in publications that were critical of the government.

Libel/Slander Laws: In contrast with the previous year, the government did not use libel laws to suppress criticism. National Security: The government used the ATP to suppress criticism. Journalists feared covering five groups designated by parliament as terrorist organizations in 2011 (Ginbot 7, the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF), the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF), al-Qaida, and al-Shabaab), citing ambiguity on whether reporting on these groups might be punishable under the law.

Internet Freedom

The state-owned Ethio Telecom was the only internet service provider in the country. The government periodically restricted access to certain content on the internet and blocked several websites, including blogs, opposition websites, and websites of Ginbot 7, the OLF, and the ONLF. The government also temporarily blocked news sites such as al-Jazeera and the BBC. Several news blogs and websites run by opposition diaspora groups were not accessible.

These included Addis Neger, Nazret, Ethiopian Review, CyberEthiopia, Quatero Amharic Magazine, Tensae Ethiopia, and the Ethiopian Media Forum. Authorities took steps to block access to Virtual Private Network providers that let users circumvent government screening of internet browsing and e-mail. Authorities monitored telephone calls, text messages, and e-mails. There were reports such surveillance resulted in arrests. According to the International Telecommunication Union, approximately 3 percent of individuals used the internet in 2014. In 2013 Citizen Lab, a Canadian research center at the University of Toronto, identified 25 countries, including Ethiopia, that hosted servers linked to FinFisher surveillance software.

According to the report, “FinFisher gained notoriety because it has been used in targeted attacks against human rights campaigners and opposition activists in countries with questionable human rights records.” A “FinSpy” campaign in the country allegedly “used pictures of Ginbot 7, an Ethiopian opposition group, as bait to infect users.” In addition to its domestic activities, the government used “FinSpy” to monitor the online activities of Ethiopians living abroad. Academic Freedom and Cultural Events The government restricted academic freedom, including through decisions on student enrollment, teachers’ appointments, and curricula. Authorities frequently restricted speech, expression, and assembly on university and high school campuses.

The ruling party, via the Ministry of Education, continued to give preference to students loyal to the party in assignments to postgraduate programs. Some university staff members commented that students who joined the party received priority for employment in all fields after graduation. Authorities limited teachers’ ability to deviate from official lesson plans. Numerous anecdotal reports suggested non-EPRDF members were more likely to be transferred to undesirable posts and bypassed for promotions. There were unspecified reports of teachers not affiliated with the EPRDF being summarily dismissed for failure to attend party meetings. There continued to be a lack of transparency in academic staffing decisions, with numerous complaints from individuals in the academic community alleging bias based on party membership, ethnicity, or religion.

A separate Ministry of Education directive prohibits private universities from offering degree programs in law and teacher education. The directive also requires public universities to align their curriculum with the ministry’s policy of a 70/30 ratio between science and social science academic programs. As a result the number of students studying social sciences and the humanities at public institutions continued to decrease; private universities focused heavily on the social sciences. Reports indicated a pattern of surveillance and arbitrary arrests of Oromo University students based on suspicion of their holding dissenting opinions or participation in peaceful demonstrations. According to reports there was an intense buildup of security forces (uniformed and plainclothes) embedded on university campuses in the period preceding the May 24 national elections.

b. Freedom of Peaceful Assembly and Association Freedom of Assembly

The constitution and law provide for freedom of assembly; however, the government did not always respect this right. Organizers of large public meetings or demonstrations must notify the government 48 hours in advance and obtain a permit. Authorities may not refuse to grant a permit but may require the event be held at a different time or place for reasons of public safety or freedom of movement. If authorities determine an event should be held at another time or place, the law requires organizers be notified in writing within 12 hours of the time of submission of their request.

The government denied some requests by opposition political parties to hold protests but permitted other requests for demonstrations. Opposition party organizers alleged government interference in most cases, and authorities required several of the protests to move to different dates or locations from those the organizers requested. Protest organizers alleged the government’s claims of needing to move the protests based on public safety concerns were not credible. There were numerous reported cases of government denial of freedom of assembly, similar to the following example. On January 25, police detained approximately 35 demonstrators at protest organized by the Unity for Democracy and Justice Party (UDJ). The UDJ claimed to have submitted proper and timely applications for permits for the protest; however, authorities alleged the rally lacked proper authorization.

Local government officials, almost all of whom affiliated with the EPRDF, controlled access to municipal halls, and there were many complaints from opposition parties that local officials denied or otherwise obstructed the schedulingof opposition parties’ use of halls for lawful political rallies. There were numerous credible reports owners of hotels and other large facilities cited internal rules forbidding political parties from utilizing their spaces for gatherings. Regional governments, including the Addis Ababa regional administration, were reluctant to grant permits or provide security for large meetings. Freedom of Association Although the law provides for freedom of association and the right to engage in unrestricted peaceful political activity, the government limited this right. The Charities and Societies Proclamation (CSO) law bans anonymous donations to NGOs. All potential donors were therefore aware their names would be public knowledge. The same was true concerning all donations made to political parties. A 2012 report by the UN special rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and association stated, “The enforcement of these (the CSO law) provisions has a devastating impact on individuals’ ability to form and operate associations effectively.” International NGOs seeking to operate in the country had to submit an application via Ethiopian embassies abroad, which the Ministry of Foreign Affairs then submitted to the Charities and Societies Agency for approval.

Elections and Political Participation Recent Elections: On May 24, the country held national elections for the House of People’s Representatives, the country’s parliamentary body. On October 5, parliament re-elected Hailemariam Desalegn prime minister. In the May national parliamentary elections, the EPRDF and affiliated parties won all 547 seats, giving the party a fifth consecutive five-year term. Government restrictions severely limited independent observation of the vote. The African Union was the sole international organization permitted to observe the elections. Opposition party observers accused local police of interference, harassment, and extrajudicial detention. Independent journalists reported little trouble covering the election, including reports from polling stations. Some independent journalists reported receiving their observation credentials the day before the election, after having submitted proper and timely applications. Six rounds of broadcast debates preceded the elections, and for the most part, they were broadcast in full and only slightly edited. The debates included all major political parties. Several laws, regulations, and procedures implemented since the 2005 national elections created a clear advantage for the EPRDF throughout the electoral process. The “first past the post” provision, or 50 percent plus one vote required to win a seat in parliament, as stipulated in the constitution, contributed to EPRDF’s advantage in the electoral process.

Nearly ONE HUNDRED churches across Canada have been torched or damaged after activists lied that 200 indigenous children were buried under Catholic schools

There were reports of unfair government tactics, including intimidation of opposition candidates and supporters. Various reports confirmed at least six election-related deaths during the period before and immediately following the elections. There were reports questioning the National Electoral Board of Ethiopia’s (NEBE)’s political independence, particularly its decisions concerning party registration and candidate qualification.”

To read the rest of the report read it HERE.

Tehdros was part of the leadership of that government.

Ethopia was a dry run for what we are seeing.

Seems like we are seeing a theme here.

Good is called evil and is punished.

Evil is called good and is rewarded.

The world is completely upside down.

https://needtoknow.news/2024/08/research-shows-claims-of-cattle-emissions-causing-climate-change-are-overblown/